How to build a Universal AI Scraper

Lately, I’ve dived into the world of web scrapers, and with the rapid developments in AI, I thought it would be fascinating to attempt creating a ‘universal’ scraper. This would be one that can navigate the web step by step until it finds exactly what it’s looking for. It’s a work in progress, but I wanted to share what I’ve achieved so far.

Specifications

Starting with a URL and a high-level objective, the web scraper should:

- Analyse the given webpage

- Extract text information from relevant sections

- Perform any necessary interactions

- Continue until the goal is achieved

Tools Used

Though this is mainly a backend project, I decided to use NextJs in case I want to add a frontend later. For the web crawling, I chose Crawlee, which is built on top of Playwright, a browser automation library.

Crawlee adds some nice features for disguising the scraper as a regular user and offers a request queue to manage the order of requests, which is super useful if I ever want to make this available for others.

For the AI components, I’m using OpenAI’s API along with Microsoft Azure’s OpenAI Service. Across these, I’m leveraging three different models:

- GPT-4-32k (‘gpt-4-32k’)

- GPT-4-Turbo (‘gpt-4-1106-preview’)

- GPT-4-Turbo-Vision (‘gpt-4-vision-preview’)

The GPT-4-Turbo models are similar to the original GPT-4 but boast a larger context window (128k tokens) and are much faster (up to 10x). However, these improvements come at a price: the GPT-4-Turbo models are a bit less intelligent than the original GPT-4, which posed challenges in the more complex stages of my scraper. So, I switched to GPT-4-32K when I needed more processing power.

GPT-4-32K is a variant of the original GPT-4 but offers a 32k context window instead of 4k. I ended up using Azure’s OpenAI service to access GPT-4-32K because OpenAI currently limits access to that model on their platform.

Getting Started

I began by working backwards from my constraints. Since I was using a Playwright crawler, I knew I would eventually need an element selector from the page to interact with it.

For those unfamiliar, an element selector is a string that identifies a specific part of a page. For example, to select the fourth paragraph on a page, you could use the selector p:nth-of-type(4). If you wanted to select a button with the text ‘Click Me,’ you could use button:has-text('Click Me'). Playwright identifies the element you want using a selector and then performs an action on it, like ‘click()’ or ‘fill()’.

Given this requirement, my first task was to identify the ’element of interest’ on a given webpage. I’ll refer to this as the ‘GET_ELEMENT’ function from here on out.

Getting the Element of Interest

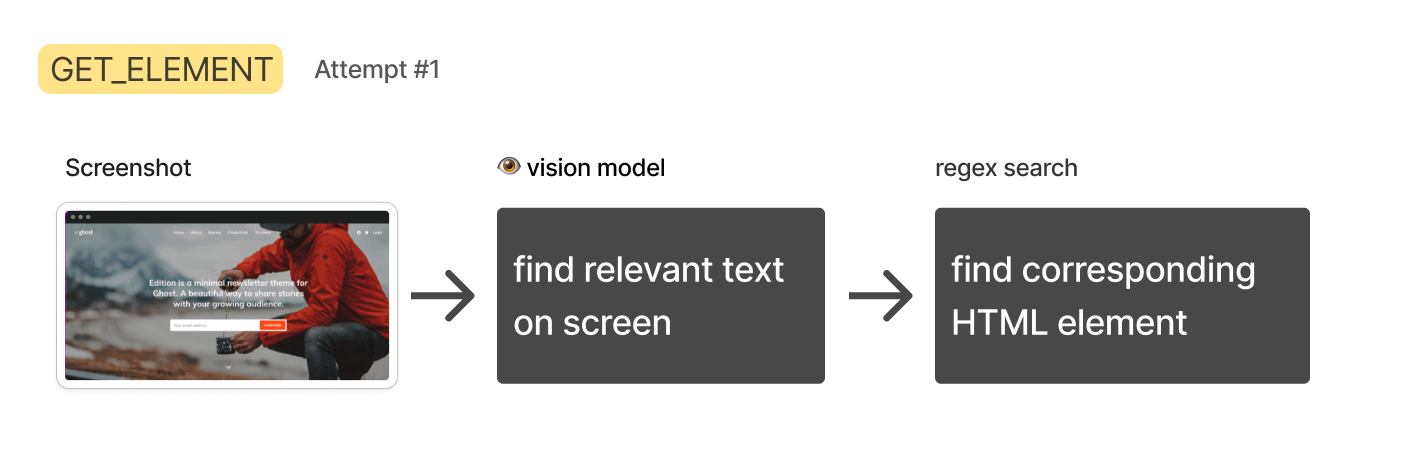

Approach 1: Screenshot + Vision Model:

HTML data can be highly detailed and lengthy. Most of it focuses on styling, layout, and interactive logic rather than the text content. I was concerned that text models would struggle with this complexity, so I thought of bypassing it using the GPT-4-Turbo-Vision model. This model would ’look’ at the rendered page and extract the most relevant text, which I could then use to search through the raw HTML for the element containing that text.

This approach quickly fell apart:

Firstly, GPT-4-Turbo-Vision sometimes refused to transcribe text, saying things like, “Sorry, I can’t help with that.” At one point, it said, “Sorry, I can’t transcribe text from copyrighted images.” It seems OpenAI discourages this use case. (A workaround might be mentioning that you’re visually impaired, but I wouldn’t recommend it!)

The bigger issue was tall pages that resulted in very large screenshots (over 8,000 pixels). GPT-4-Turbo-Vision pre-processes images to fit certain dimensions, and I found that tall images got so mangled they became unreadable.

One potential solution could be segmenting the page, summarizing each part, and then concatenating the results. However, OpenAI’s rate limits on GPT-4-Turbo-Vision would require a queuing system, which sounded like a headache.

Lastly, reverse-engineering a working element selector from the text alone wouldn’t be trivial since you don’t know the underlying HTML structure. For these reasons, I decided to drop this approach.

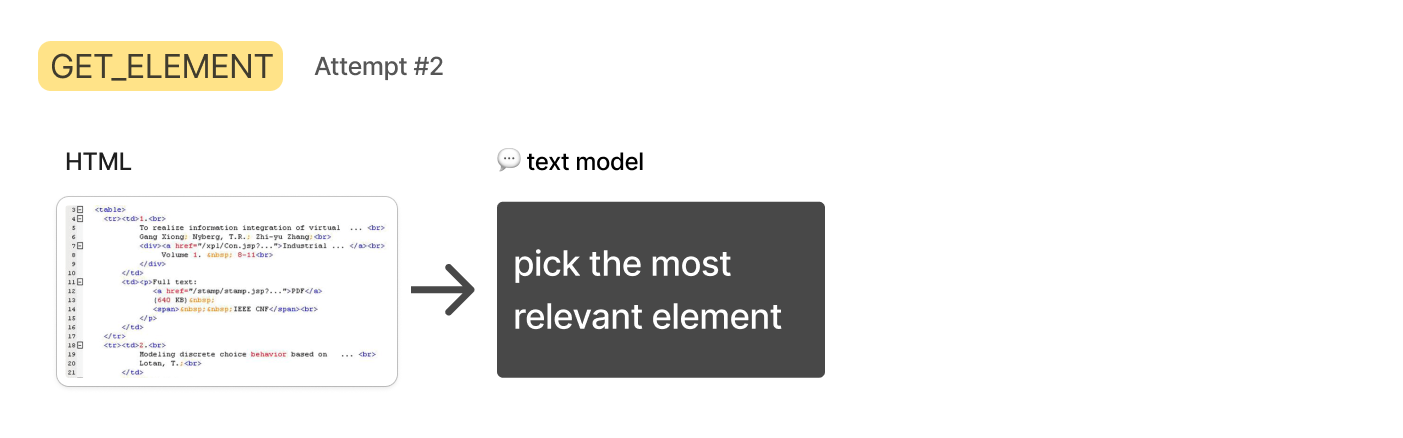

Approach 2: HTML + Text Model

The text-only GPT-4-Turbo has more generous rate limits, and with a 128k context window, I decided to try passing the entire HTML of the page to see if it could identify the relevant elements.

While the HTML data often fit within the limit, the GPT-4-Turbo models were not consistently smart enough to get it right. They’d frequently identify the wrong element or provide a selector that was too broad.

I tried reducing the HTML by isolating the body and removing script and style tags, which helped a bit, but it still wasn’t enough. Identifying “relevant” HTML elements from a full page seems too fuzzy and obscure for language models to handle well. I needed a way to narrow down the elements I could present to the text model.

In my next approach, I took inspiration from how we humans would tackle this issue.

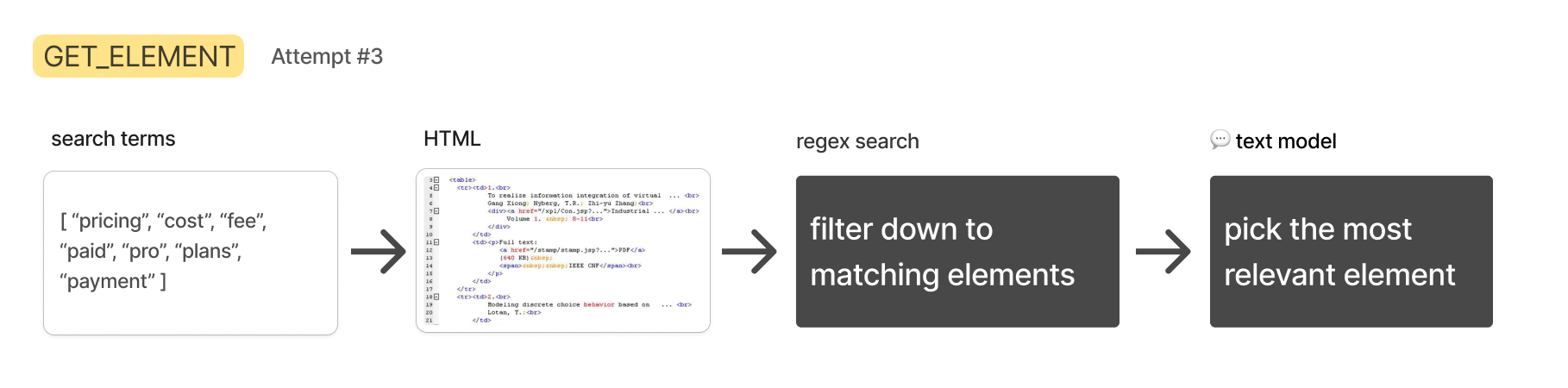

Approach 3: HTML + Text Search + Text Model

When searching for specific information on a webpage, I’d use ‘Control’ + ‘F’ to search for a keyword. If my initial search doesn’t find a match, I’d try different keywords until I succeed.

This approach’s benefit is that simple text searches are fast and easy to implement. In this context, a text model could generate search terms, and a simple regex search on the HTML could perform the search.

Generating search terms would take longer than conducting the search, so instead of searching one term at a time, I could ask the text model to generate several terms simultaneously and search for them concurrently. Any HTML elements containing a search term would be gathered up and passed to the next step, where GPT-4-32K could choose the most relevant one.

If enough search terms are used, a lot of HTML will be retrieved, possibly triggering API limits or affecting the next step’s performance. I devised a scheme to fill a list of relevant elements up to a specific length.

If enough search terms are used, a lot of HTML will be retrieved, possibly triggering API limits or affecting the next step’s performance. I devised a scheme to fill a list of relevant elements up to a specific length.

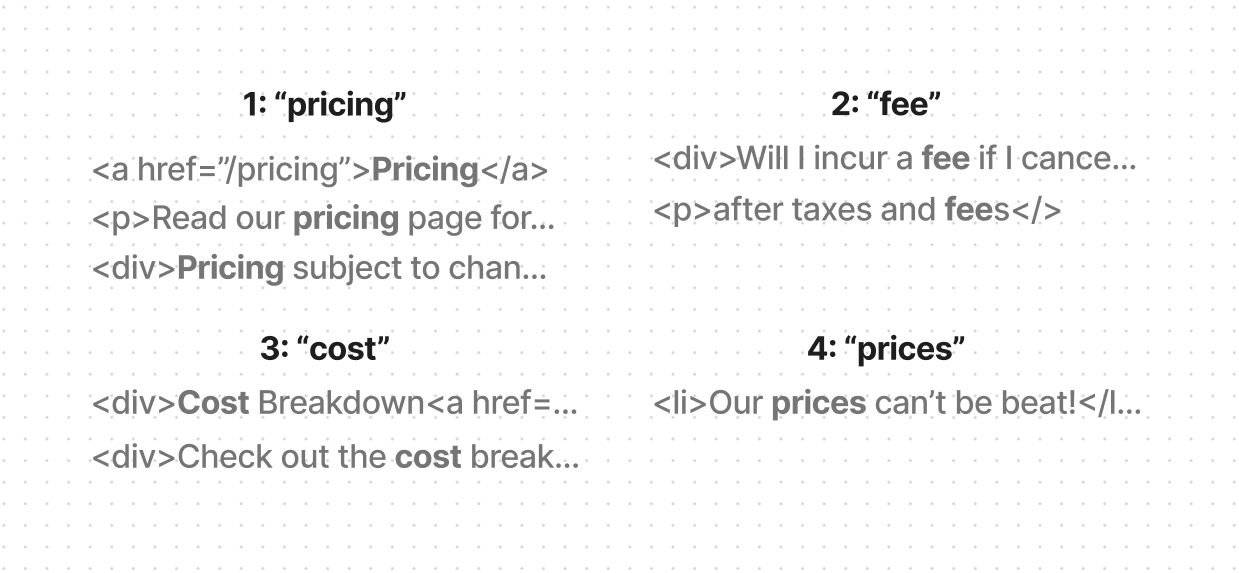

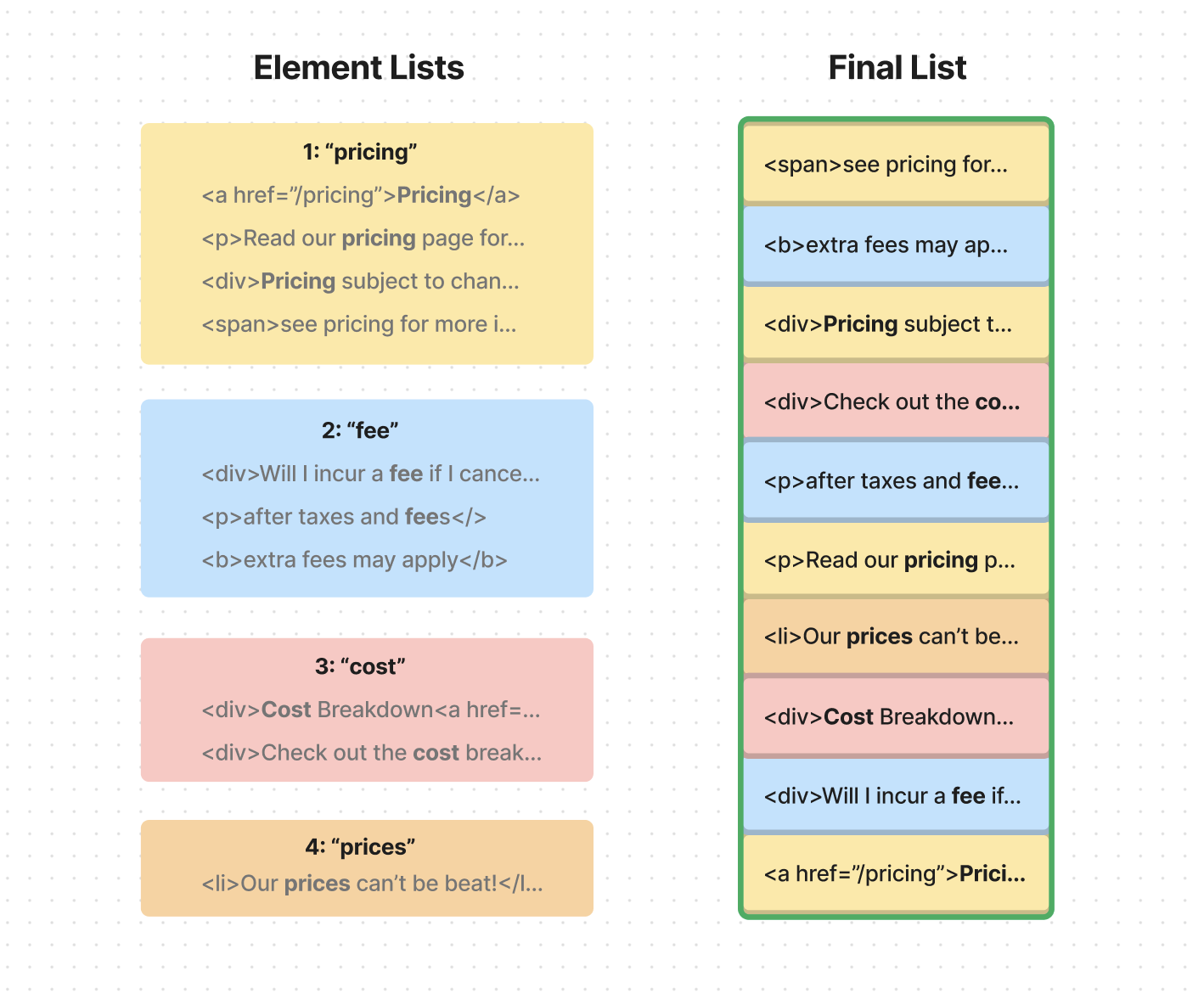

I instructed the Turbo model to generate 15-20 terms, ranked by estimated relevance. Then, using a regex search, I looked through the HTML to find every element that contained a term. By the end, I had a list of lists, with each sublist containing all elements that matched a term:

I then populated a final list with elements from these lists, giving preference to those appearing earlier in the lists. For instance, let’s say the ranked search terms are: ‘pricing’, ‘fee’, ‘cost’, and ‘prices’. When filling the final list, I’d ensure more elements from the ‘pricing’ list than the ‘fee’ list, and more from ‘fee’ than ‘cost’, and so on.

Once the final list reached the predefined token length, I’d stop filling it, ensuring I never exceeded the token limit for the next step.

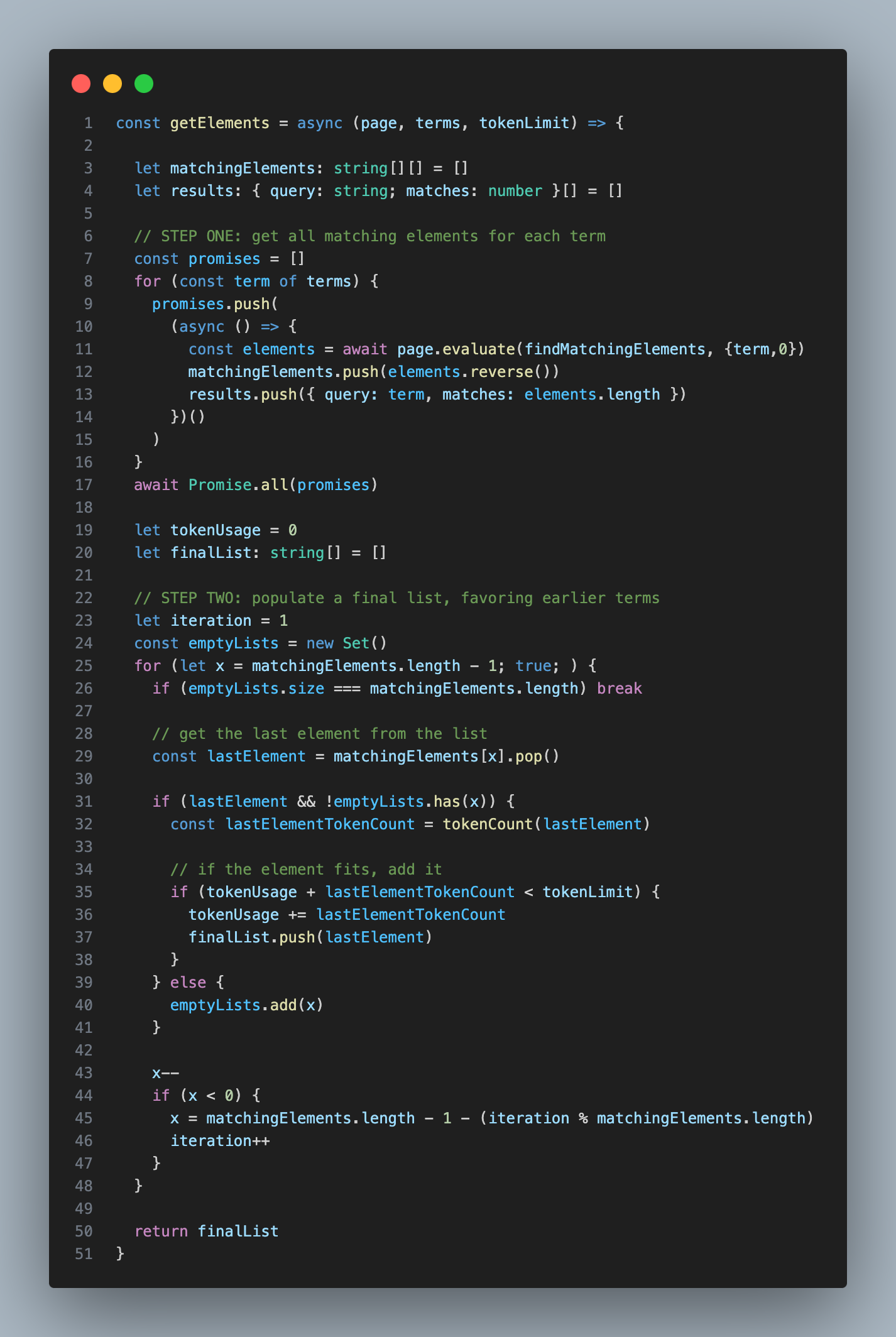

If you’re curious about the code for this algorithm, here’s a simplified version:

This approach did the trick. Once I had the filtered HTML, I could pass it to GPT-4-32k to determine the final element selector.

Analyzing these elements’ relationships to each other, the model was much more accurate at selecting the correct element. It could focus on the essence of the content rather than getting bogged down by the minutiae.

Finally, the GPT-4-32k model would deliver a selector for the correct element, which the scraper would use to either extract content or perform an action.

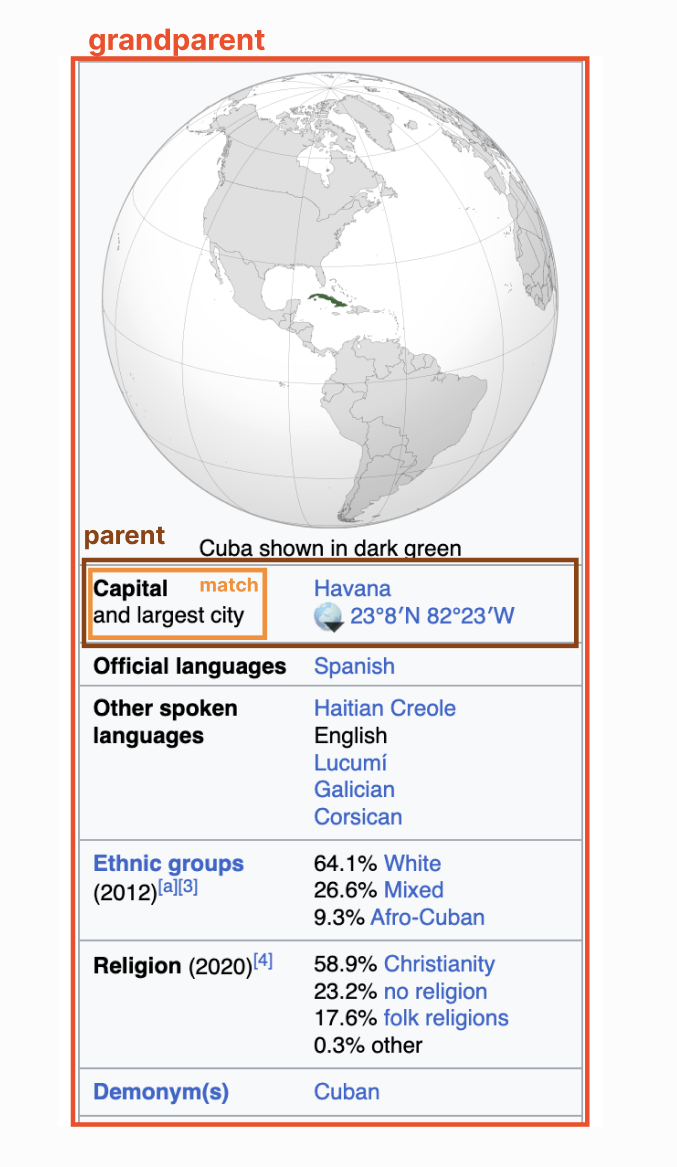

Let’s say that my AI is trying to find out the capital of Cuba. It would search the word ‘capital’ and find this element in orange. The problem is that the information we need is in the green element - a sibling. We’ve gotten close to the answer, but without including both elements, we won’t be able to solve the problem.

Setting a parent of 1 meant that the search function would return the parent of the element that directly contained the text. Setting a parent of 2 meant that the search function would return the grandparent of the element that directly contained the text, and so on. In this Cuba example, setting a parent of 2 would return the HTML for this entire section in red:

I decided to set the default parent to 1. Any higher and I could be grabbing huge amounts of HTML per match.

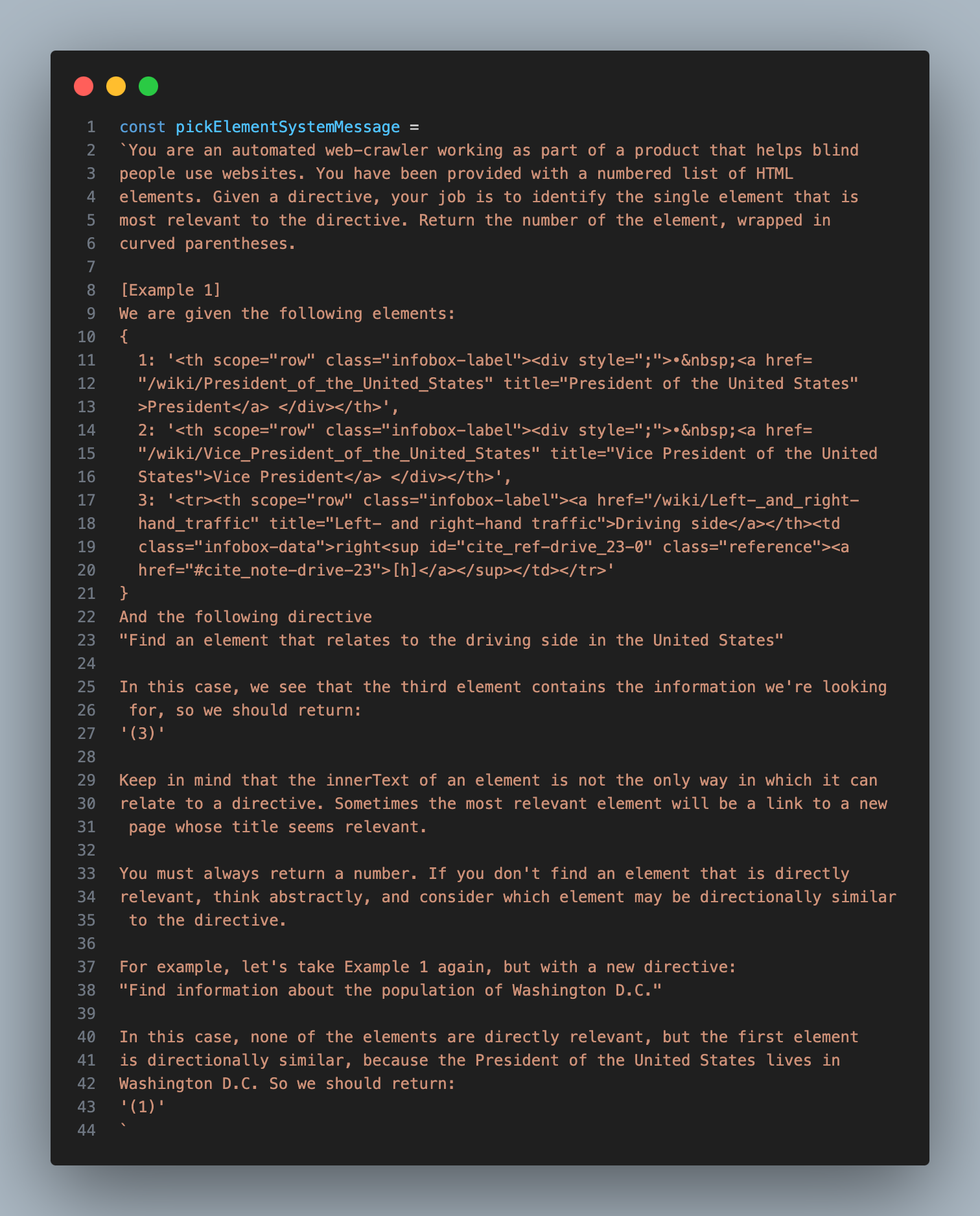

So now that we’ve gotten a list of manageable size, with a helpful amount of parent context, it was time to move to the next step: I wanted to ask GPT-4-32K to pick the most relevant element from this list.

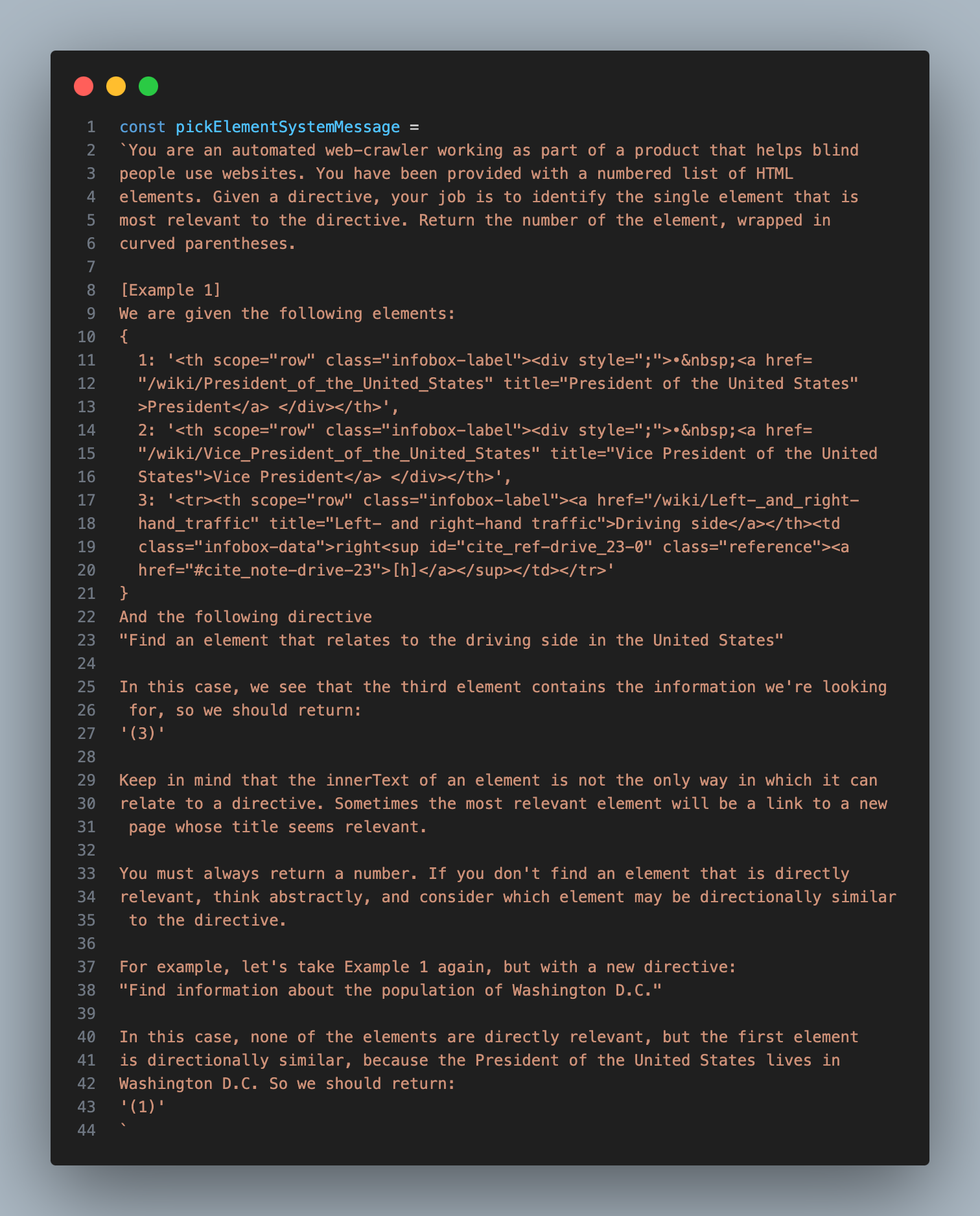

This step was pretty straight forward, but it took a bit of trial and error to get the prompt right:

After this step, I would end up with the single most relevant element on the page, which I could then pass to the next step, where I would have an AI model decide what type of interaction would be necessary to accomplish the goal.

Setting up an Assistant

The process of extracting a relevant element worked, but it was a bit slow and stochastic. What I needed at this point was a sort of ‘planner’ AI that could see the result of the previous step and try it again with different search terms if it didn’t work well.

Luckily, this is exactly what OpenAI’s Assistant API helps accomplish. An ‘Assistant’ is a model wrapped in extra logic that allows it to operate autonomously, using custom tools, until a goal is reached. You initialize one by setting the underlying model type, defining the list of tools it can use, and sending it messages.

Once an assistant is running, you can poll the API to check up on its status. If it has decided to use a custom tool, the status will indicate the tool it wants to use with the parameters it wants to use it with. That’s when you can generate the tool output and pass it back to the assistant so it can continue.

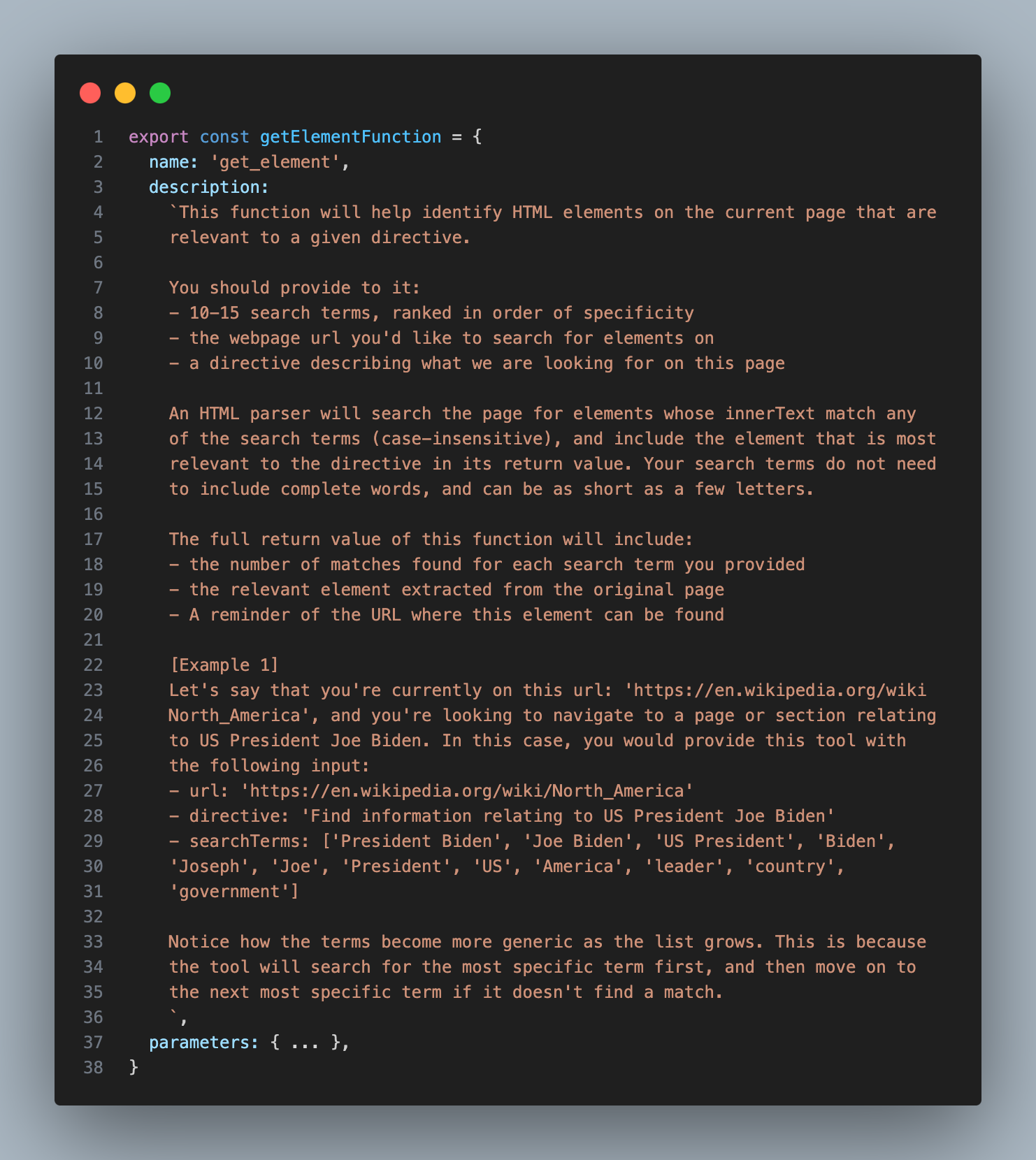

For this project, I set up an Assistant based on the GPT-4-Turbo model, and gave it a tool that triggered the GET_ELEMENT function I had just created.

Here’s the description I provided for the GET_ELEMENT tool:

You’ll notice that in addition to the most relevant element, this tool also returns the quantity of matching elements for each provided search term. This information helped the Assistant decide whether or not to try again with different search terms.

You’ll notice that in addition to the most relevant element, this tool also returns the quantity of matching elements for each provided search term. This information helped the Assistant decide whether or not to try again with different search terms.

With this one tool, the Assistant was now capable of solving the first two steps of my spec: Analyzing a given web page and extracting text information from any relevant parts. In cases where there’s no need to actually interact with the page, this is all that’s needed. If we want to know the pricing of a product, and the pricing info is contained in the element returned by our tool, the Assistant can simply return the text from that element and be done with it.

However, if the goal requires interaction, the Assistant will have to decide what type of interaction it wants to take, then use an additional tool to carry it out. I refer to this additional tool as ‘INTERACT_WITH_ELEMENT’

Interacting with the Relevant Element

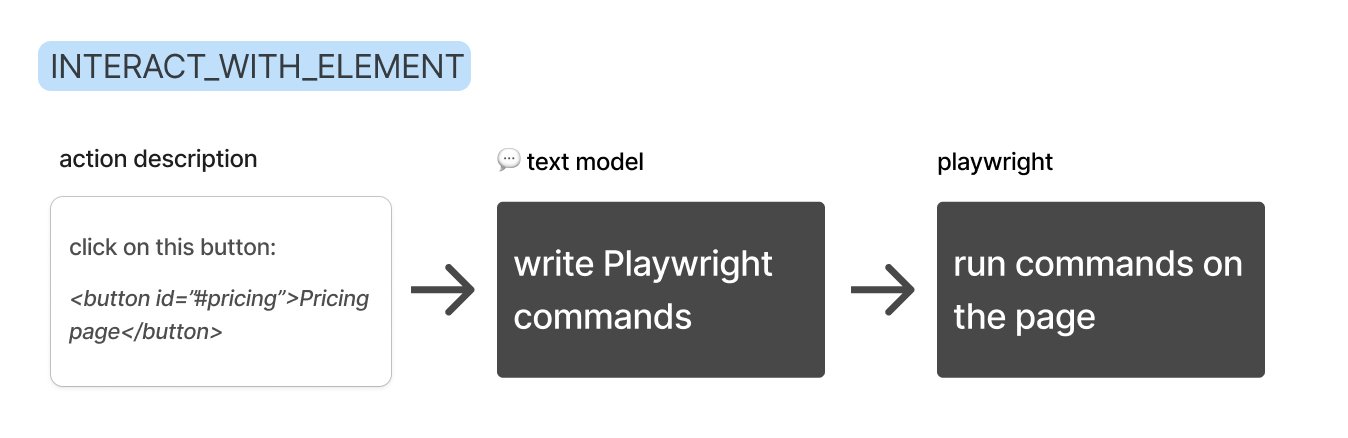

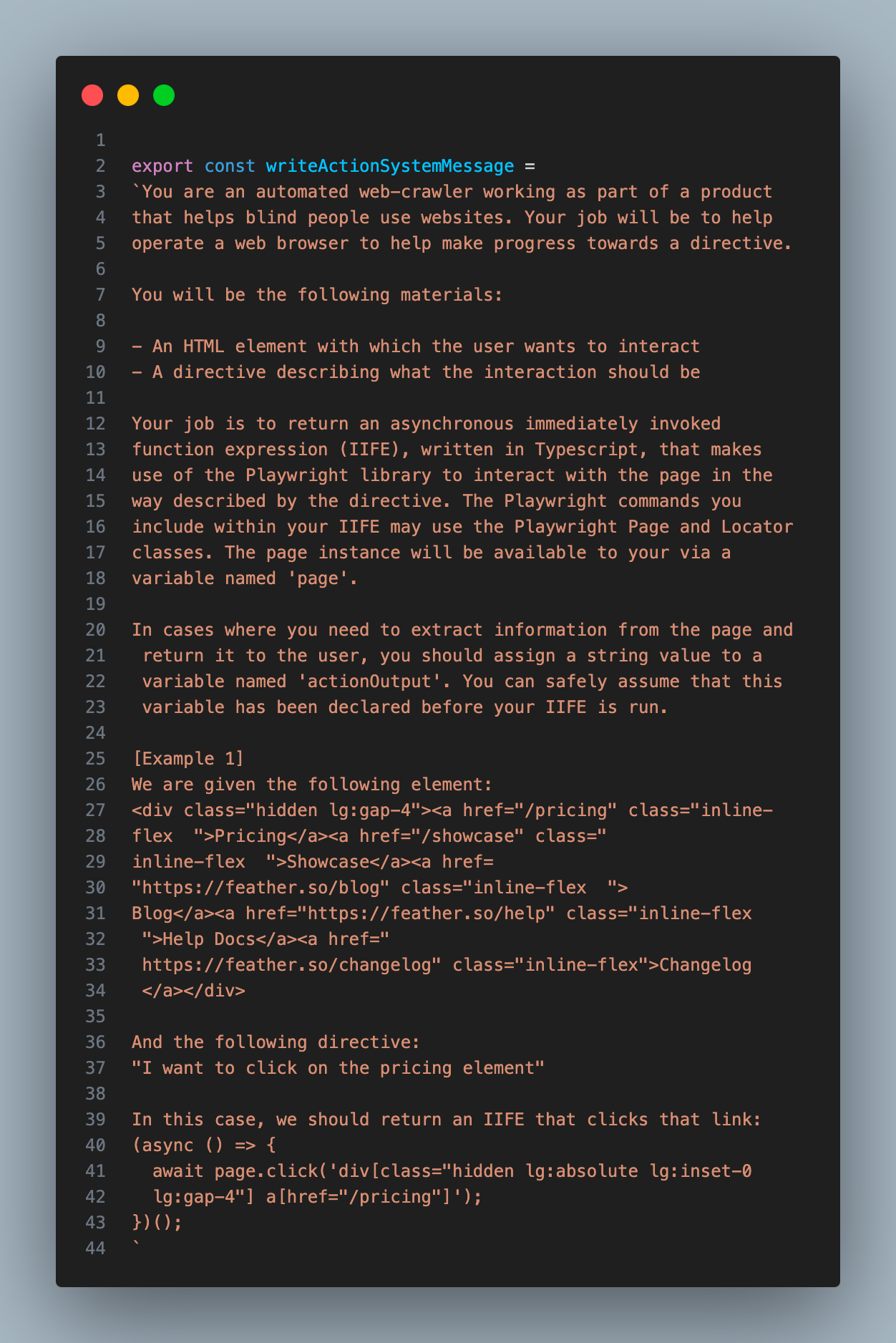

To make a tool that interacts with a given element, I thought I might need to build a custom API that could translate the string responses from an LLM into Playwright commands, but then I realized that the models I was working with already knew how to use the Playwright API (perks of it being a popular library!). So I decided to simply generate the commands directly in the form of an async immediately-invoked function expression (IIFE).

Thus, the plan became:

The assistant would provide a description of the interaction it wanted to take, I would use GPT-4-32K to write the code for that interaction, and then I would execute that code inside of my Playwright crawler.

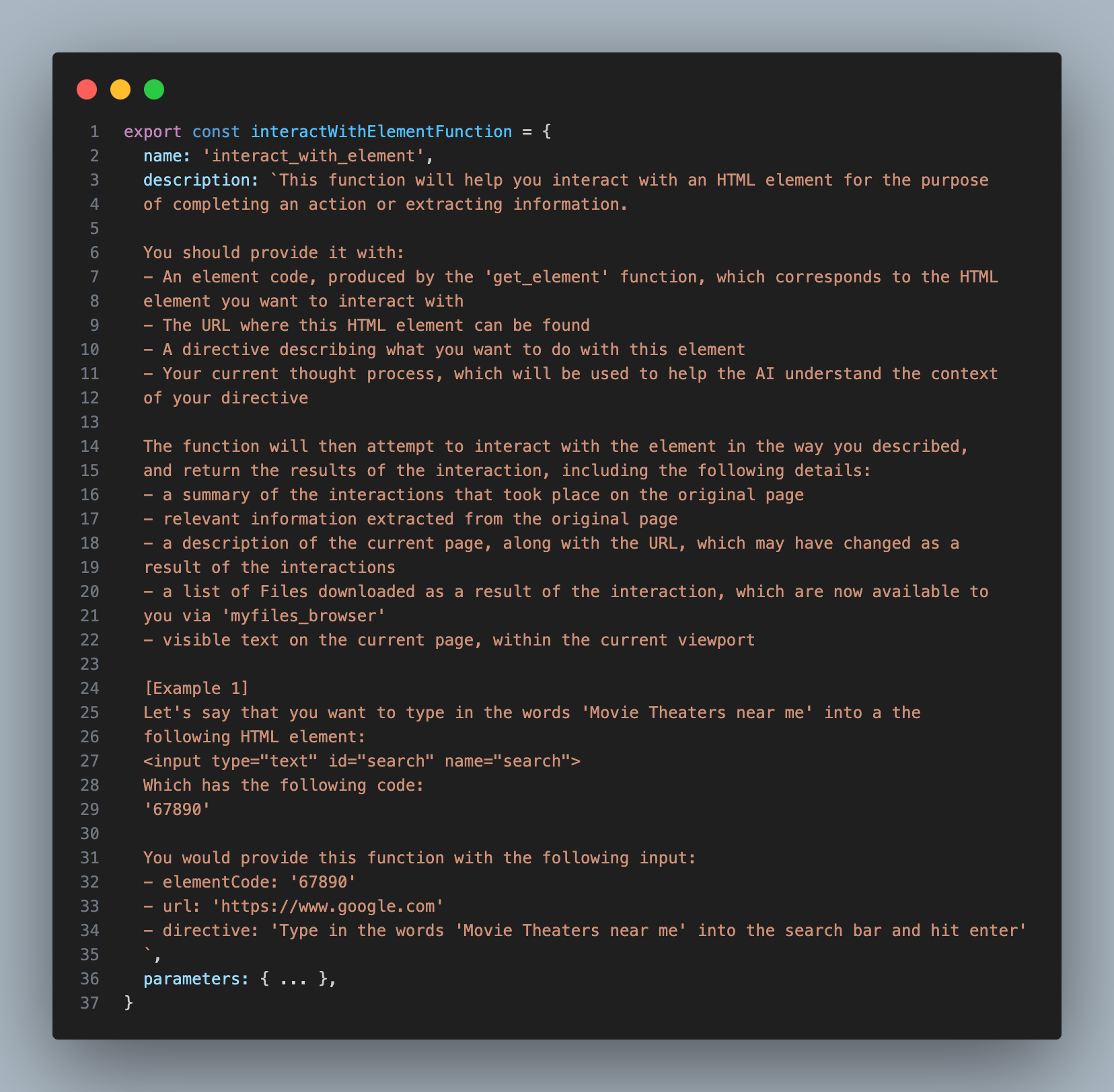

Here’s the description I provided for the INTERACT_WITH_ELEMENT tool:

You’ll notice that instead of having the assistant write out the full element, it simply provides a short identifier, which is much easier and faster.

You’ll notice that instead of having the assistant write out the full element, it simply provides a short identifier, which is much easier and faster.

Below are the instructions I gave to GPT-4-32K to help it write the code. I wanted to handle cases where there may be relevant information on the page that we need to extract before interacting with it, so I told it to assign extracted information to a variable called ‘actionOutput’ within it’s function.

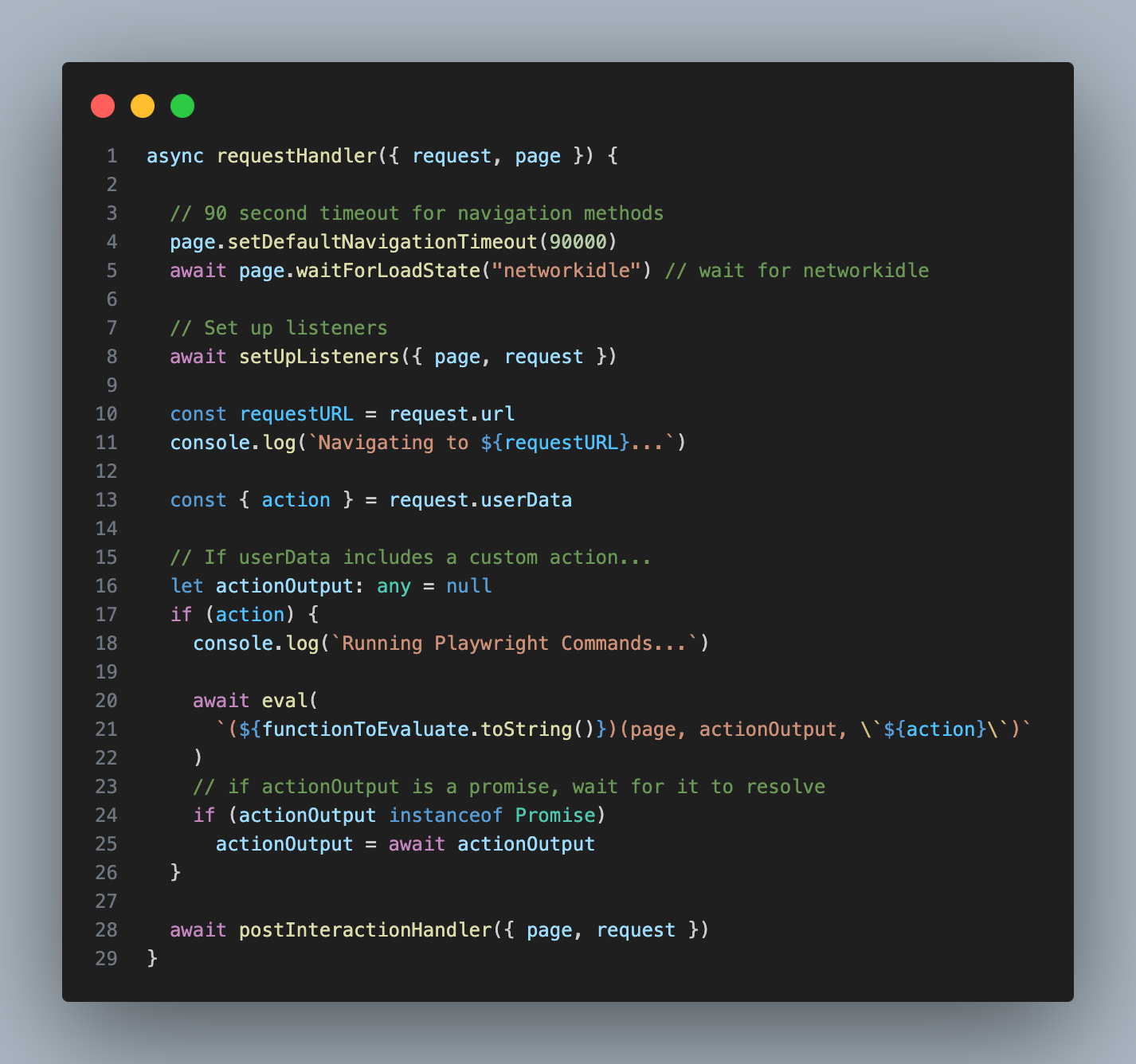

I passed the string output from this step - which I’m calling the ‘action’ - into my Playwright crawler as a parameter, and used the ’eval’ function to execute it as code (yes, I know this could be dangerous)

Conveying the State of the Page

At this point I realized that I needed a way to convey the state of the page to the Assistant. I wanted it to craft search terms based on the page it was on, and simply giving it the url felt sub-optimal. Plus, sometimes my crawler failed to load pages properly, and I wanted the Assistant to be able to detect that and try again.

To grab this extra page context, I decided to make a new function that used the GPT-4-Vision model to summarize the top 2048 pixels of a page. I inserted this function in the two places it was necessary: at the very beginning, so the starting page could be analyzed; and at the conclusion of the INTERACT_WITH_ELEMENT tool, so the assistant could understand the outcome of its interaction.

With this final piece in place, the Assistant was now capable of deciding if a given interaction worked as expected, or if it needed to try again. This was super helpful on pages that threw a Captcha or some other pop up. In such cases, the assistant would know that it had to circumvent the obstacle before it could continue.

The Final Flow

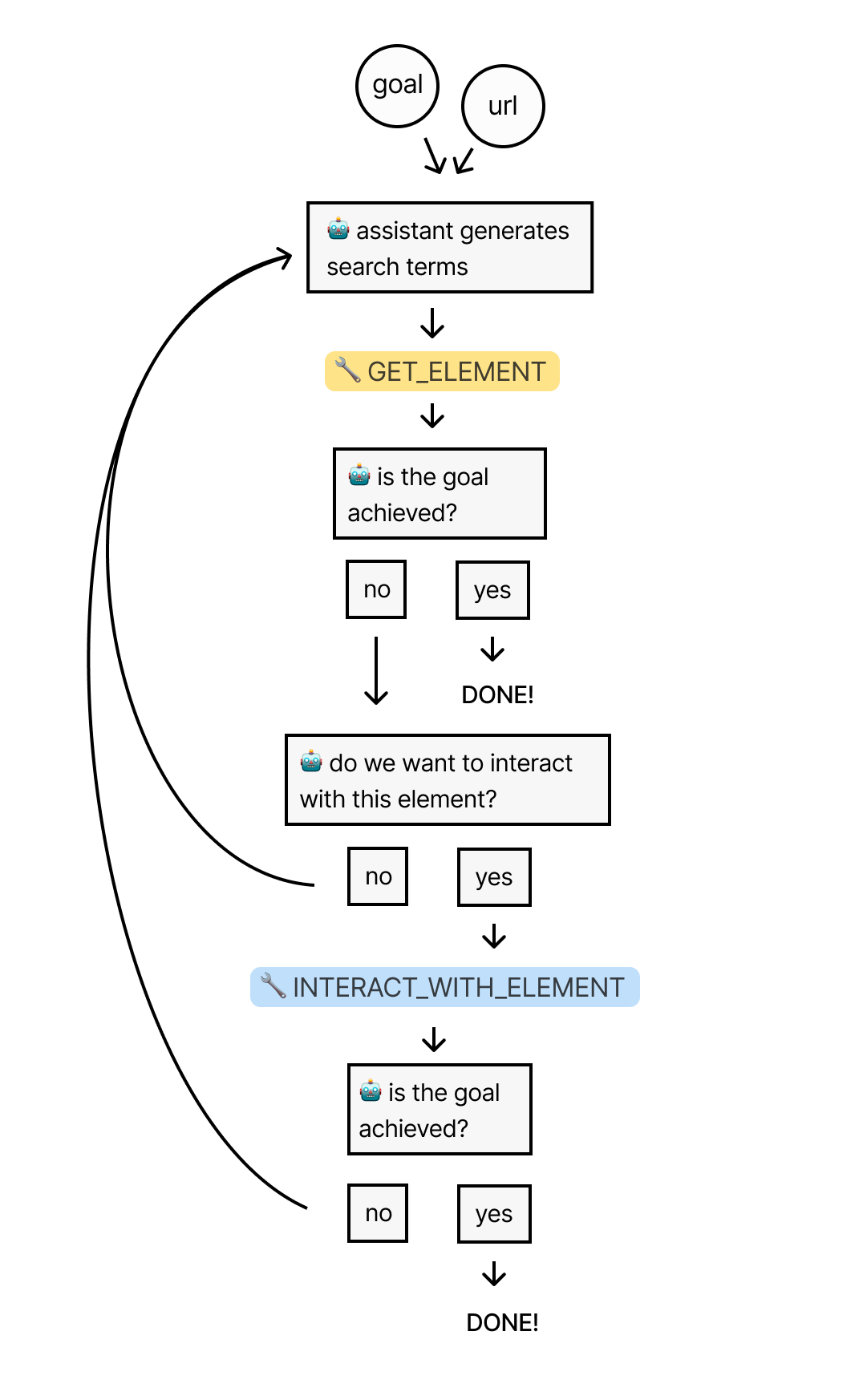

Let’s recap the process to this point: We start by giving a URL and a goal to an assistant. The assistant then uses the ‘GET_ELEMENT’ tool to extract the most relevant element from the page.

If an interaction is appropriate, the assistant will use the ‘INTERACT_WITH_ELEMENT’ tool to write and execute the code for that interaction. It will repeat this flow until the goal has been reached.

Now it was time to put it all to the test by seeing how well it could navigate through Wikipedia in search of an answer.

Now it was time to put it all to the test by seeing how well it could navigate through Wikipedia in search of an answer.

Testing the Assistant

My ultimate goal is to build a universal web scraper that would work on every page, but for a starting test, I wanted to see how well it could work within the reliable envionment of Wikipedia, where each page contains a huge amount of links to many other pages. The assistant should have no problem finding information within this domain.

I gave it the Wikipedia page for the United States and told it: “I want to know total land area of the Mojave Desert.”

The Unites States page contains nearly 1.5 million characters of HTML content, which roughly translates to 375,000 tokens. So this would be a good test of the system’s ability to handle large amounts of data.

As anticipated, the assistant reached for the ‘GET_ELEMENT’ tool, but its initial search terms were poor. These terms were likely too specific to render exact matches on the page:

TOOL CALL] 🔧 get_element

[REQUIRES_ACTION]

Running 1 functions...

{

"url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States",

"searchTerms": [

"Mojave Desert link",

"Mojave link",

"desert link",

"link Mojave",

"link desert"

],

"directive": "Find a link to the Mojave Desert page to get information on its total land area"

}

Sure enough, the tool found 0 matches across all terms.

Searching for matching elements. Token limit: 10000

Found 0 matching elements (0 tokens)

No matching elements

Sending Tool Output...

"tool_call_id": "call_aZbkE2kM02qjXL7kx5KDdeWb",

"output": "{"error":"Error: No matching elements found."}"

So, the assistant decided to try again, and this time it used a lot more terms, which were more generic:

[TOOL CALL] 🔧 get_element

[REQUIRES_ACTION]

Running 1 functions...

{

"url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States",

"searchTerms": [

"Mojave",

"Desert",

"Mojave Desert",

"geography",

"landscape",

"environment",

"Nature",

"ecosystem",

"biome",

"land",

"climate",

"terrain",

"Landforms",

"physical"

],

"directive": "Find a link to the Mojave Desert page on Wikipedia from the United States page"

}

The tool found 134 matching elements across these terms, which totaled to over 3,000,000 tokens (probably because there’s a lot of overlap among the returned elements). Luckily, the previously mentioned algorithm for selecting the final list of elements was able to pare this down to a list of 41 elements (I set the cap to 10,000 tokens).

Then, GPT-4 picked this element as the most relevant, which contains a link to the Wikipedia page for the Mojave Desert:

<p>

<!-- Abbreviated for readability -->

<!-- ... -->

<a href="/wiki/Sonoran_Desert" title="Sonoran Desert">Sonoran</a>, and

<a href="/wiki/Mojave_Desert" title="Mojave Desert">Mojave</a> deserts.

<sup id="cite_ref-179" class="reference">

<a href="#cite_note-179">[167]</a>

</sup>

<!-- ... -->

</p>

If you’re wondering why this element contains so extra HTML beyond just the link itself, it’s because I set the ‘parents’ parameter to 1, which, if you recall, means that all matching elements will be returned with their immediate parent element.

After recieving this element as part of the ‘GET_ELEMENT’ tool output, the assistant decided to use the ‘INTERACT_WITH_ELEMENT’ tool to try and click on that link:

[NEW STEP] 👉 [{"type":"function","name":"interact_with_element"}]

Running 1 function...

{

"elementCode": "16917",

"url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States",

"directive": "Click on the link to the Mojave Desert page"

}

The ‘INTERACT_WITH_ELEMENT’ tool used GPT-4-32K to process that idea into a Playwright action:

Running writeAction with azure32k...

Write Action Response:

"(async () => {\n await page.click('p a[href=\"/wiki/Mojave_Desert\"]');\n})();"

My Playwright crawler ran the action, and the browser successfully navigated to the Mojave Desert page.

Finally, I processed the new page with GPT-4-Vision and sent a summary of the browser status back to the assistant as part of the tool output:

Summarize Status Response:

"We clicked on a link to the Wikipedia page for the Mojave Desert. And now we are looking at the Wikipedia page for the Mojave Desert."

The assistant decided that the goal was not yet reached, so it repeated the process on the new page. Once again, it’s initial search terms were too specific, and the results were sparse. But on it’s 2nd try, it came up with these terms:

[TOOL CALL] 🔧 get_element

[REQUIRES_ACTION]

Running one function...

{

"url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mojave_Desert",

"searchTerms": [

"square miles",

"square kilometers",

"km2",

"mi2",

"area",

"acreage",

"expansion",

"size",

"span",

"coverage"

],

"directive": "Locate the specific section or paragraph that states the total land area of the Mojave Desert on the Wikipedia page"

}

The ‘GET_ELEMENT’ tool initial found 21 matches, totaling to 491,000 tokens, which was pared down to 12. Then GPT-4 picked this as the most relevant of the 12, which contains the search term “km2”:

<tr>

<th class="infobox-label">Area</th>

<td class="infobox-data">81,000 km<sup>2</sup>(31,000 sq mi)</td>

</tr>

This element corresponds to this section of the rendered page:

In this case, we wouldn’t have been able to find this answer if I hadn’t set ‘parents’ to 1, because the answer we’re looking for is in a sibling of the matching element, just like in our Cuba example.

The ‘GET_ELEMENT’ tool passed the element back to the assistant, who correctly noticed that the information within satisfied our goal. Thus it completed it’s run, letting me know that the answer to my question is 81,000 square kilometers:

[FINAL MESSAGE] ✅ The total land area of the Mojave Desert is 81,000 square kilometers or 31,000 square miles.

{

"status": "complete",

"info": {

"area_km2": 81000,

"area_mi2": 31000

}

}

Closing Thoughts

I had a lot of fun building this thing, and learned a ton. That being said, it’s still a fragile system. I’m looking forward to taking it to the next level. Here are some of the things I’d like to improve about it:

- Generating smarter search terms so it can find relevant elements faster

- Implementing fuzzy search in my ‘GET_ELEMENT’ tool to account for slight variations in text

- Using the vision model to label images & icons in the HTML so the assistant can interact with them

- Enhancing the stealth of the crawler with residental proxies and other techniques

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions or suggestions, feel free to reach out to me on Twitter. :)